I contributed a bit of reporting to this story written by Ian Fullerton. It was originally published in Skyline on September 29, 2010. I covered the closing of the original location of Pie Hole Pizza Joint for the Medill News Service in May 2010.

New address, same concerns

Pie Hole Pizza Joint gets chilly welcome from new neighbors

09/29/2010 10:00 PM

By IAN FULLERTON, Contributing Reporter

LAKEVIEW

Doug Brandt never expected that his pizza shop would become a refuge for the city’s gay black youth. But now that it has, he’d like to keep it that way, despite the protests of some Boystown residents and local businesses.

Brandt is the owner of the Pie Hole Pizza Joint, a popular Lakeview restaurant soon to be reopened at 3477 N. Broadway.

Pie Hole previously had sat for years at the corner of Roscoe and Halsted, in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer mecca known as Boystown. Brandt, a 39-year-old marketing major from Iowa with experience in sales, bought the struggling pizza joint in early 2007, with the hopes of revitalizing the shop through smart, often sexually charged advertising and innovations such as “drag delivery,” which is exactly what it sounds like.

Tired of catering to the late night set, Brandt looked to target the early evening dinner crowd, the not-yet-too-drunk demographic that seemed a better fit for the 15-seat restaurant. And so Pie Hole started running a weekly karaoke night, which caught on. Soon after, the shop started hosting open mic nights, aptly titled “Soul at the Hole.”

The events quickly attracted a younger following — vocalists, spoken-word artists, musicians and a variety of other performers, mostly high school and college-age youth from all parts the city — who flocked to Pie Hole once a week to take to the stage.

“It wasn’t a huge money maker,” said Brandt. “It was just a really cool, chill night with amazing talent.”

And while the open mic and karaoke drew a wide array of participants and spectators, it soon became clear that Pie Hole’s customer-base was rooted in the cluster of LGBTQ African-American youth who came from around the city to Boystown.

•

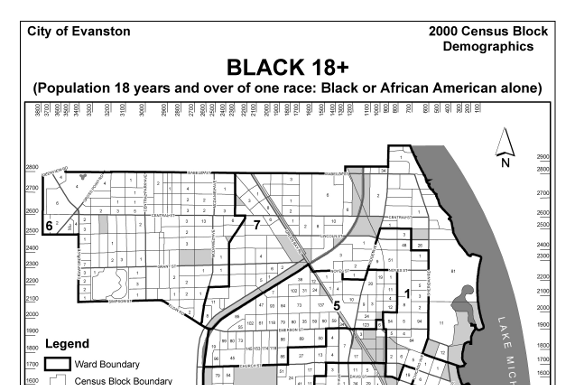

Population estimates compiled by the Metro Chicago Information Center, based on data from EASI, Inc., a demographic research company, show that African Americans make up only about 5 percent of the population of Lake View, the community area that includes Boystown.

These same statistics show 12- to 17-year-olds make up the smallest age segment. Together with 18 to 24 year olds, they make up about 17 percent of the community area’s population, which is still less than half of the percentage of 25 to 34 year-olds, the group that dominates the neighborhood.

These numbers may come as a surprise to anyone strolling on the main drag of Boystown around Halsted and Belmont, where African-American youths gather in droves, not in the bars and clubs, but on the streets.

The city’s young LBGTQ African-American population from elsewhere in the city is attracted to Boystown in part because of the protection that the neighborhood provides, said Ryan Erickson, a community relations and outreach manager at the Center on Halsted.

“It’s one of the most prominent places in the city where you don’t have to really worry about how you’re sexual orientation is going to be received,” he said. “I think that certainly offers a degree of security.”

A few months after opening Pie Hole, Brandt had started to volunteer at the recently opened Center on Halsted, a community center for LGBTQ persons based in Boystown. At the Center, Brandt took a training course and was assigned to the youth program, where he mentored a young man.

“It felt kind of cool,” said Brandt. “It kind of clicked that this could be the cause for Pie Hole; this could be the thing where we could say ‘yes, we give back to the community.’”

The restaurant began donating pizzas to youth organizations such as the Broadway Youth Center and the South Side-based Youth Pride Services, while inviting kids from the programs to hang out at the shop.

“It quickly became apparent that a lot of the kids didn’t have a place to go,” he said.

As the popularity of the performances at Pie Hole grew, so too did the crowds. The atmosphere at times shifted from a sit-down pizza joint to that of a standing-room club, with groups sometimes pouring out on to the sidewalk in front of the restaurant.

What followed was inevitable. Nearby residents, businesses — and sometimes Brandt himself — began calling 911 to complain of noise disturbances, loitering and fights outside the shop and in the neighboring alley.

Brandt hired some of the teens to act as security guards at the events, a service that further drained his pockets, but the performance nights became more financially unfeasible, as most of the audience wasn’t buying anything.

“It got to the point where I was paying $400 or $500 to have karaoke night, but I wasn’t making that back,” he said. Eventually Brandt had to shut down the karaoke, a decision that came down hard on the teens who frequented the event.

In May 2009, Brandt’s lease on the property expired, without an option to renew.

To memorialize the closing of the hangout, teens from the Youth Pride Services program put on a drum-line performance outside of the shop, a final hurrah that drew sneers from a few neighbors who didn’t appreciate the evening procession, Brandt said.

But while he realized he couldn’t keep the shop at Roscoe and Halsted, Brandt knew that he wanted to keep Pie Hole alive somewhere. He started to look for a new location, preferably one with a layout that would allow him to better supervise the audiences and keep out non-paying customers. The location on Broadway fit that need, he said.

Situated between a Save Rite pharmacy and a laundromat, the space, though only a few blocks away from the old shop, is in a markedly different environment.

Brandt learned this the hard way when, two weeks ago, he received an e-mail — not sent to him directly, but on which he was copied — regarding the reopening of his business in the more residential part of Boystown.

The e-mail, sent by the resident group Belmont Harbor Neighbors to Alderman Helen Shiller (46th), described community concerns that the relocation of Pie Hole to its new location might be an unsettling prospect, referencing the 911 calls made at the Roscoe spot.

“Belmont Harbor neighbors believes that behaviors should be confronted or stopped,” the letter read, “not shifted away from the Halsted entertainment strip to a more residential strip within the BHN boundaries.”

The author urged to Shiller to invite Brandt and the building’s landlord to appear before the group’s board of directors to present a business plan for the new Pie Hole, and to discuss how they intended “to prevent a recurrence of problems as experienced at the previous location.”

The following week, Brandt made his presentation to a group of about 20 people, mostly business owners. Among other questions, he said, they asked him what he would do if lines of customers formed outside of his shop.

“I hope I have a line down the block and around the corner 24 hours a day,” Brandt said, recalling the meeting.

A few days later, Brandt received another e-mail — again, not addressing him directly — from the president of a homeowner’s association at a nearby building.

“We don’t need or want bad actors in our residential area,” the letter read. “We are sure that our neighbors, including business owners feel the same.”

Brandt said he understood that people would have concerns about a late-night establishment, but recognized that a few vocal opponents made up a small minority of the neighborhood.

“We’re in a position to reopen, which is good for the economy and good for the neighborhood,” he said. “We’re employing people, putting out a product and giving options to the neighborhood.”

Brandt said he expected Pie Hole to retain its clientele, and promised that the open mic nights would also return, though not immediately.

The shop’s Facebook page, which boasts 1,763 followers, displays daily comments from friends and residents hailing the shops return.

“I think we’re going to pick up right where we left off,” said Brandt.

The reopening of Pie Hole Pizza Joint at 3477 N. Broadway is slated for Oct. 1.